In the ongoing conversation about climate change and carbon, a lot is being said about large-scale “solutions,” because many people seem to think that only large-scale strategies can deal with a problem as large as the one we face. Without devaluing the contributions that could be made by large-scale projects, I’d like to take a decentralized, grass-roots (literally!) look at what we can all do to bring living systems into the mix. Let’s start with some background:

Components of Soil

Soil is made up of the same kinds of components as we are, only put together differently and in different proportions.

- Minerals (particles of material weathered from rock), divided by size into sand, silt and clay, makes up most of the volume of most soils.

The different sizes and shapes create spaces for other soil components, like:

- Water

- Air (underground life needs to breathe, too)

- Organic matter (anything that is or was living)

Soil Organic Matter is CARBON

Most of the soils we use have between 0 and 10% organic matter in the top 10cm or so of depth. Unfortunately, our agricultural soils have lost about half of that. This is a significant part of the carbon dioxide emissions created by our conventional farming practices. If we can get that carbon back into the soil, and then some, we can sequester a lot of carbon dioxide in the soil. And even if you’re not a large scale farmer, you can put the same principles to use in your own yard and garden. Here’s how it works:

Tillage and keeping the soil bare removes carbon from the soil through several mechanisms:

- Exposing the soil organic matter to air allows it to oxidize into carbon dioxide (the air in soil pores contains much less oxygen that the air we breathe).

- Killing the soil organisms, physically through tillage or through habitat destruction.

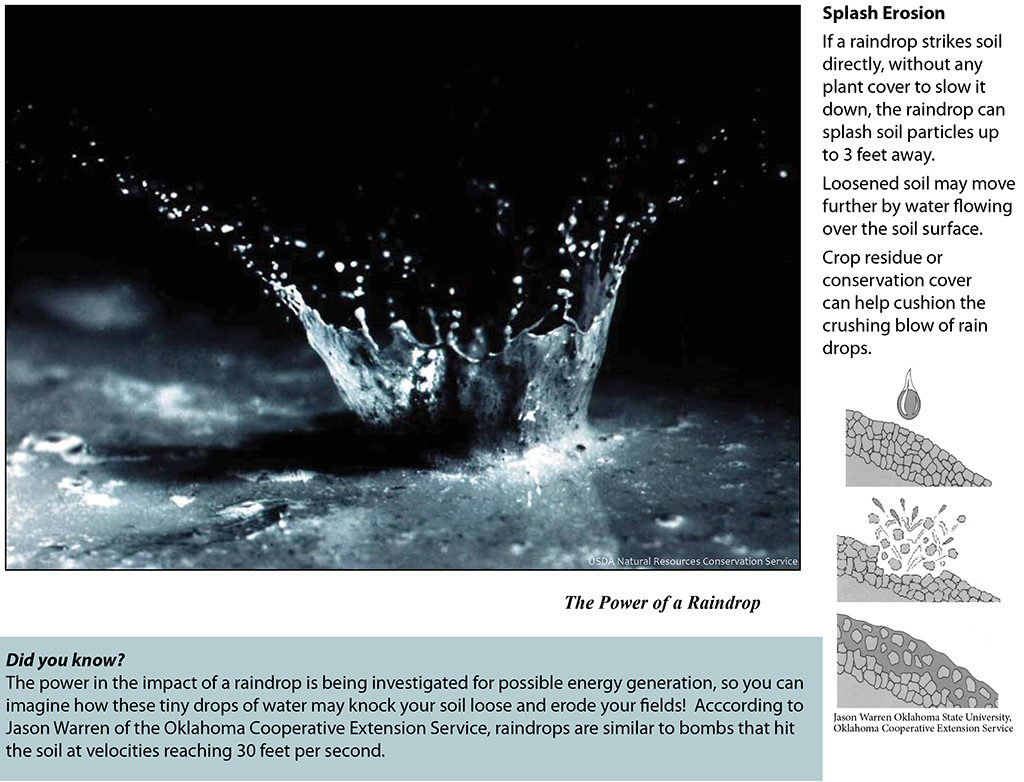

- Erosion by wind and water physically carries the organic matter away. Even tiny raindrops can be incredibly destructive!

Bare soil also loses moisture – this talk explains the links between soil carbon, water management, and climate.

The First Step: Cover Your Soil!

Whether your soil is covered by living or dead plant material (aka mulch), covering the soil provides many benefits:

- Temperature and moisture regulation (a nice blanket keeps fluctuations under control, making life easier for plants and soil organisms)

- Protection from erosion

- Reduces weeds (nature hates a vacuum) – no sun on the weed seeds means no germination

- Provides food for microbes throughout the year

These are all wonderful things, but it’s mostly on the surface. The best way to get carbon into the soil in a more stable form is through LIFE.

The Soil Food Web

Your organic material/mulch is part of what provides the base of life in the soil: food for microbes. One teaspoon (1 gram) of rich garden soil can hold up to one billion bacteria, several yards of fungal filaments, several thousand protozoa, and scores of nematodes (The Secret Life of Soil). Bacteria (which perform uncountable functions with various soil nutrients and processes) and fungi (which excel at decomposing carbon-rich plants – without them we would be kilometers deep in dead trees) will use your mulch as a source of food, water, and home, while liberating nutrients and protecting the health of your plants by outcompeting pests. They also create incredibly important direct relationships with plant roots.

Bacteria from the genus Rhizobium build colonies within special nodes on the roots of legumes (such as clover, peas, beans, alfalfa) which produce nitrogen that the plant can use from nitrogen gas available in the air (in return for sugars from the plant). Nitrogen, as the Green Revolution showed, is one of the primary limiting factors in plant growth. Fungi called mycorrhizae form relationships with at least 90% of plants (that’s some evolutionary success for you!), providing the plant with minerals and other nutrients that would otherwise not be available to it (again, in return for some sugar). The injection of these sugars (carbohydrates, yet another form of carbon) into the soil is one of many ways that plants can sequester carbon in your soil.

More and more research is showing that these relationships are the norm under the soil surface, rather than the exception, and that our agricultural soils’ poverty of microbes is in large part responsible for the declining nutritional value of our food. (for a more entertaining – and beautiful – version see Symphony of the Soil)

Further Benefits from Perennial Systems

All of these relationships can benefit your garden while putting carbon back into the soil. However, there is a further strategy you can use to add organic material to the soil in perennial systems, or even just a few perennial plants in your annual garden.

All plants like to maintain a certain root:shoot ratio, a balance between the biomass above the ground and below. It only makes sense that they only need a certain amount of root mass to feed the plant above, and vice versa. When you cut the plant above ground, in an effort to maintain its preferred ratio, it will ‘cut off’ enough of its own roots to stay comfortable. This not only adds carbon to the soil, it helps maintain soil structure, because the ‘channel’ the root formed in the soil remains even after the root itself is cycled into the food web. This helps water infiltration, which is critical.

Using the permaculture tactic of “chop and drop,” we can feed the soil from below (jettisoned roots) while feeding the soil from above (using the biomass we just chopped as mulch on the surface). This is especially potent when using leguminous plants (including caraganas ;)), because the abandoned roots contain those nitrogen-rich nodes. Geoff Lawton, in his Greening the Desert project, used a ratio of 9:1 (leguminous trees to food producing trees), repeatedly cutting the legumes to provide a steady stream of vital soil resources to the food crops. A word of caution: this is also a mechanism through which you can kill plants. Without the time to recover, the plant has no resources to replace the lost tissue and set aside the energy it needs to survive winter. Always observe to make sure you’re not overtaxing your plants (unless this is a management tool to get rid of something you don’t want).

Many farmers are beginning to use Holistic Management practices (developed by Allan Savory – here’s his TED talk) to rotate grazing animals in a way that takes advantage of this as well. These systems have the added benefit that what gets “dropped” on the soil is manure, which contains forms of nutrients that are much more readily available to plants. Point of interest: upcoming Holistic Management course at Deep Roots Permaculture!

Closing

As permaculture enthusiasts, we do our best to foster living systems that support each other and support us, and it can sometimes be hard to tell whether we’re actually reaching our regenerative goals. Geoff Lawton says in his video Permaculture Soils (and probably elsewhere) that an easy measure of your system’s success is that you’re building soil, rather than depleting it. And, whether you attribute the quote to Bill Mollison or Geoff Lawton, it remains true that “all the world’s problems can be solved in a garden.”

Recommended Resources

Other blog posts: Soil Building 101 and Git Along, Little Microbes!

Teaming with Microbes by Jeff Lowenfels & Wayne Lewis

Symphony of the Soil – documentary