When I took my permaculture design course several years ago, I learned about creating ‘guilds’ of plants. The concept may have been explained more thoroughly at the time, but what I took away and remembered was merely the technique of planting clumps of various perennials beneath and around larger trees. But it’s only recently that I started to ask myself: Why is this idea important to permaculture?

Among the various definitions of permaculture out there, David Jacke proposes this one: permaculture is the design of human cultural systems that mimic natural ecosystems (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOx06AEJVa0). We take natural ecosystems as our model because they display a plethora of desirable features (stability, resilience, abundant yields, absence of waste, self-maintenance, etc.), and they remind us that human culture and its systems are, after all, part of nature. So we permaculturists design gardens that mimic the self-maintenance characteristics (among other things) of a forest ecosystem (hence ‘food forests’ or ‘edible forest gardening’ ). And one key feature of a healthy forest is its biodiversity, with a dozen or so deciduous or coniferous tree species as the canopy, and many more plant species in the understory. From this consideration alone emerges the design imperative to cram together as many plant species as possible within the available space, hence guilds.

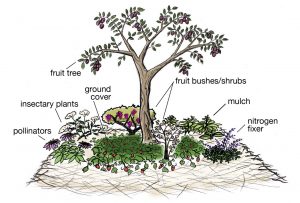

So, if we merely create guilds as random combinations of plant species, the diversity alone will give the resulting system major resilience advantages over a monoculture. But we can do better than random combinations. First, the ecosystem will be more stable if the component plants occupy distinct need-based niches, so they aren’t in competition with each other for resources. For example, if you’ve planted a large fruit tree, you don’t want to plant another large tree right next to it, competing with it for sunlight. Better a guild that puts together plants that can share the sunlight: under the large trees we plant shade-tolerant shrubs, then herbaceous perennials, and finally ground-cover species. To a large extent, these differences in plant height are mirrored by differences in root depth, and so guild members chosen according to height will also minimize competition for water in the soil.

So far so good, but guild members so-chosen merely share the space. The hallmark of a natural ecosystem is the rich symbiotic relationships that exist among the component species. So we can also choose guild members according to the distinct yield-based niches that they occupy: mulch-makers, nitrogen-fixers, nutrient accumulators, and insect (and other fauna) attractors (these categories taken from a handout by Claudia Bolli). But there will often be unforeseen symbiotic relationships that emerge as well. David Jacke gives the example of an indirect symbiosis between grape vines and raspberries. Both plants’ are subject to infestation by the leaf-hopper insect, but raspberries leaf out earlier than grapes, and so populations of parasitic wasps which develop early in the season to attack leaf-hoppers on the raspberries are still around later to protect the grapes. Grapes grown in a monoculture system, by comparison, may be devastated by leaf-hoppers, because it’s too late at that point for the parasitic wasp populations to develop. This guild-like relationship between raspberries, grapes, and the insects they attract, can function even though the raspberres and grapes are planted hundreds of feet apart! Which brings me back to my original point about maximizing biodiversity: the greater the diversity of the guilds we create, the more of these ‘freebie’ symbiotic relationships we can expect to emerge, even though they were not specifically designed into the system at a conscious level.

Good design principles for a garden are often good for human communities as well. I was not involved in the decision, a few years ago, to rename our ‘Society’ as the ‘Edmonton Permaculture Guild’, but I find the word ‘guild’ entirely fitting, in light of the reflections above, for the kind of permaculture community we’re striving to nurture here in Edmonton. There’s a niche here for everybody; and the more diversity we can foster among us the better.

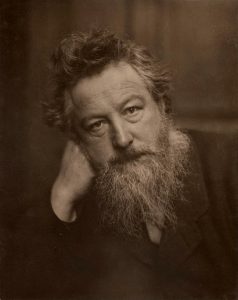

I also appreciate the way the term harkens back to the craft guild system of late mediaeval Europe. As the nineteenth century art critic, historian and political philosopher William Morris argued (in, for example, The Revolt of Ghent), these guilds served as effective systems of mutual aid among the artisan class in the burgeoning cities during this period, and they exerted a strong democratic influence on late mediaeval society (contributing, for example, to the disappearance of serfdom). Morris coined the term ‘guild socialism’ to describe his political philosophy, as an alternative to the centralized government-based socialism advocated by Marxists, among others.

Unfortunately, the guild socialism of late mediaeval Europe was crushed by alliances of national monarchies, merchant elites and large feudal landholders that morphed into the capitalist class (see Kevin Carson’s Studies in Mutualist Political Economy chapter 4, available at http://www.mutualist.org/id71.html). Perhaps the permaculturists’ resurrection of the guild concept, and its extension to social structures, informed by awareness of economic history, can be the springboard for a profound transformation towards a more free, just and sustainable way of life for all of us.